Manipulative Play

It's interesting to hear people talk about play. While we all know play when we see it, some speak of it as a way for young children to learn, as a catalyst to breed cooperation, interpersonal relationships, coordination, and as the very foundation for life success. Amazingly, there are still those who think play is trivial, simply time off from the things that children should be doing, like book study, structured events, and ensuring adherence to educational standards. Both views think their opinion states what children need in order to be successful adults.

Ask children why they play, and we get to the heart of the matter. They will tell you, "I do it to have fun, to spend time with friends, because I like it." To a child, play is simply a choice they make that is fun, enjoyable, and self motivated. While time for it may be planned, the activities that happen during that time rarely are, they simply unfold, which is what children dearly love, but don’t always know how to articulate that play is their own time, free from the guidance of adults, interference in the development of their games and imaginations, and based on the child's sense of what's real and what's important and relevant now. This child-centered definition of play is what upsets the balance of those who try to assign adult objectives to child-focused activity. Play is maddening to some, because they feel there are no quantitative adult objectives that are met. Outcomes are difficult to measure. Specific academic skills and goals seem unrelated.

Add to this conundrum the fact that children are often directed to video games as a way to play, keeping them "safe at home" and efficiently acting as babysitters; however, these activities lack the experiential focus so beloved and fondly remembered by their parents and grandparents. Tapping away on a lighted screen doesn’t provide the sight, sound, and experience of jumping in leaf piles, racing through the woods, or turning over stones to discover little creatures. Slaying dragons in online games doesn’t provide the competition, strategic thinking, and exhilaration that playing “capture the fort” does. Jumping a character across the war-torn tundra in a video game doesn’t offer the speed, rushing wind, or physical conditioning that using a playground swing or slide can create. In fact, new studies from the University of Montreal suggest that too many hours of video gaming can have adverse effects on the brain, and while video gamers may exhibit "efficient visual attention abilities, they are also much more likely to use navigation strategies that rely on the brain's reward system (the caudate nucleus) and not the brain's spatial memory system (the hippocampus). Past research has shown that people who use caudate nucleus-dependent navigation strategies have decreased grey matter and lower functional brain activity in the hippocampus.

So as we continue to observe children's "activity" being funneled into passive, little electronic boxes as a means of experience and competition, and as we watch school curriculum outweigh the need for outdoor playground experiences, how do we advocate for children and play?

Linking the correlation between learning and play is certainly important. By observing children and play and analyzing what is happening, people may be able to better embrace the concept of play as learning, and learning as a broader concept than the typical "three R's."

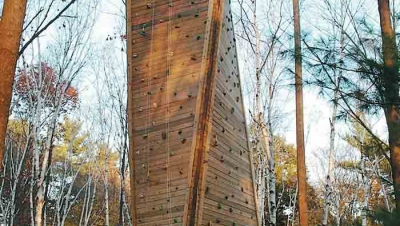

Physical play provides opportunities to develop fine and gross motor skills, promote muscular development, coordination, and physical conditioning. Physical play also promotes endurance in active settings. Physical play and development are critical for education, besides allowing children time to expend stored energy and refocus effort on academia. A recent study suggests that obese children are actually slower than healthy-weight children to recognize when they have made an error and correct it. The research is the first to show that weight status not only affects how quickly children react to stimuli but also impacts the level of activity that occurs in the cerebral cortex during action monitoring. In the study, the scientists measured the behavioral and neuroelectric responses of preadolescent children, half of them obese, half at a healthy weight. Children were asked to press a button to denote a response. Obese children were found to be considerably slower to respond and that healthy-weight children were better at evaluating their need to change their behavior in order to avoid future errors. This adds to the research by Rima Shore in 1997 that confirmed the critical link between stimulating activity and brain development.

Social play helps children learn how to act and interact with others, while learning important lessons in reciprocity, give and take, turns, listening vs. talking. Without these skills, children's behavior in a classroom setting is sure to suffer.

Creating things with found items plays a vital role in learning, and can identify skills that lead to builders, artists, marketers, and other creative occupations. Constructive play allows for experimentation, cause and effect, failure leading to new approaches to a problem, and control of the environment around them.

Play really is a curriculum in and of itself and a road map for creativity and learning. Simply stated, when children play, they learn. Children who play learn better academically. Look at the Sudbury School examples highlighted in an earlier column. In a school where play is the curriculum, students show no lag in testing, college readiness, or workforce performance post graduation.

Play encourages creativity, cooperation, innovation, and self-awareness. Play develops us and prepares us for real life in a way no other activity or curriculum can. We must continue to advocate for, defend, develop, and promote playful behavior and opportunities by continuing to learn about play, advocating for it in our schools and parks, and engaging in playful behavior throughout our lives. We'd love to hear how you're advocating for play. Please add your comments in the field below.