Researchers say kindergarteners don’t get enough play; why it’s critical to do something about it...

As a culture, we are dedicated to rearing our children to be the best, boldest, and most educated kids on the block.

However, this upswing in public achievement-based childhood development is driving an academic culture of “results above all else.”

While the pursuit of achievement is admirable, a group of researchers is arguing for a change of pace. It seems the more we push our kids, teachers, and schools to give us the superlative in early childhood education, the more we seem to fail our youngest children in the very thing that will support them—and those in the playground industry—in our quest for bright, capable kids. What are we missing in our test-fueled journey to that enviable A+? The freedom to play.

Three new studies released in March 2009 by the non-profit organization Alliance for Childhood drive home the point that developmentally vital kindergarten playtime is nearly extinct.

According to the Alliance for Childhood, researchers from UCLA, Long Island University and Sarah Lawrence College in New York found the troubling development that kindergarteners from New York and Los Angeles were being subjected to near daily standardized tests and at least 2-3 hours of instruction and testing in literacy and math.

Tests Vs. Playtime?

These timeframes for testing represent a striking increase over educational tactics used previously. Alliance directors Edward Miller and Joan Almon, co-authors of the book Crisis In The Kindergarten, Why Children Need to Play in School, released the study findings as a call to arms for education policy makers and administrators to reassess the educational value of children’s playtime in the play-wasteland that has become our nation’s kindergartens—at least some of them.

The Alliance directors voiced concerns over the findings that even the very materials available to children (blocks, sand, dramatic play props) have been replaced with their less-than-joyful counterparts— standardized tests. Most troubling are the results that playtime—if kids are given any at all—is less than 30 minutes per day. The playground industry itself should especially take note, since much of what is built in terms of playgrounds occurs on school property. Those tax dollars and fundraiser monies can easily find a new funnel if schools stop presenting the need for playground equipment.

Yes, schools are beleaguered to meet educational standards despite dwindling budgets and higher costs. As a result, many schools zeroed in on cutting recess as a way to meet NCLB goals. Teachers too have additional requirements and opting out of playtime in favor of lessons, on the surface, seems like a logical choice, since it’s just playtime, right?

Wrong. It’s just not what the doctor ordered. There is a mounting body of research that points to play as the very foundation of a child’s ability to learn. However, Almon pointed out that teachers are discouraged from creative classroom instruction and play as a means of making sure kids meet test criteria.

“If the teachers are taught how to support play, it quickly becomes evident how much they (the children) learn,” Almon said. She also said that some teachers have increasingly begun to rely on scripted teaching methods as opposed to livelier educational play, calling this change “the antithesis of a creative, good learning environment.”

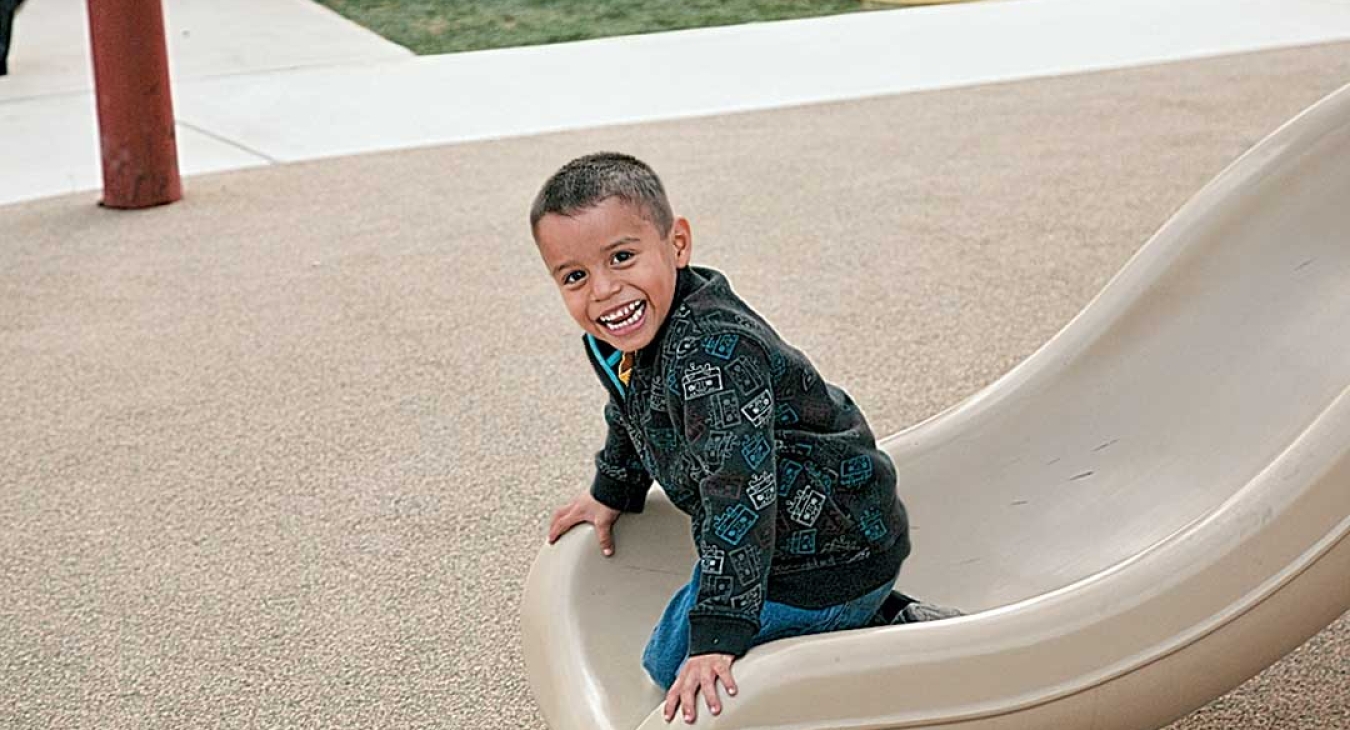

Playgrounds Develop Potential

The best playgrounds are rich in many types of play opportunities, to suit the many different developmental needs of kids.

“Children need a broad repertoire of play,” Almon said. “Playgrounds need a broad repertoire of play. They do well with large motor play, but they do need small motor play and rumble-tumble play. Each kind of play is needed to help develop a child and their abilities.”

Despite the meager amount of playtime built into the typical school curriculum and on the playground, she said kids can do enormous amounts with very little. Rocks, sticks, and a pail of water, and a good 20 minutes can make for an incredibly imaginative play opportunity.

“The playground is the perfect place for this,” she said. It’s arguable that a sort of recommended daily allowance of playtime be parceled out to kids with their morning Flintstone vitamins. Even so, recess time is in danger and some schools have opted out of offering recess altogether. A recent Pediatrics study

However well-intentioned, legislators are also looking at the possibility of extending early childhood learning requirements to America’s pre-schools—a movement that Almon finds potentially alarming. Yes, there are definite merits to providing early education to children; however, child advocates warn the structure and so-called “downward push” to educate these youngsters carries with it a requisite bureaucracy with an inevitable need to produce measurable results—possibly meaning more tests for even younger kids.

Lose Playtime, Lose Big?

If early childhood play experiences actually create new synaptic pathways in the brains of children, how can the American educational system continue to deny play to children who stand to benefit most from rich play experiences? In the book, Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination and Invigorates the Soul, by Stuart Brown and Christopher Vaughn, they argue that play is the “single most important factor in determining success and happiness.”

As members of the playground industry, it is arguable that the case for play needs to be revisited and its demonstrated importance presented to school administrators, child advocates, and other decision-makers. In an era that values achievement, robbing our youngest citizens of crucial playground moments—moments that have demonstrated an increase in higher developmental gains—comes across as a society gone astray.

The differences in the outcomes among the most play-deprived children, like those in the Romanian orphanages who are tied to beds and only allowed a few minutes of playtime a day, versus their counterparts in other countries that value play are stark. Romanian orphans experience severe delays in neurological development and on average their brains have been found to be up to 30 percent smaller than their same-age peers.

A Healthy Development

If those findings aren’t enough, a 2007 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics, “The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds,”

Despite this need, it said the percentage of schools offering recess went from 96 percent in 1989 to 70 percent in 1999. But, the problem isn’t just an American one. In 2007, 270 international child therapists and other child professionals collectively signed a letter to the U.K. Telegraph blaming a “lack of play” for the collective worsening mental health of the international community of children.

There are, however, signs that the tide of thinking just might be beginning to change course. One playground company has started up its own campaign, the Peaceful Playgrounds National Right to Recess Campaign. It aims to help individuals and communities advocate play/recess to school boards across the country even as it calls the current idea of eliminating recess “a really bad idea.”

School administrations nationwide are reassessing the need for recess. The playground industry, as benefactors of every child’s inherent need to play, might want to speak up on behalf of the children who utilize their playground equipment. There are a handful of examples where playground companies, along with their organization IPEMA are doing that very thing.

As Almon said, “I think educators and school administrators need to take some time to study the value of play. It is a critical element of childhood.”

Add new comment