Wake of sniper attacks raise questions about new threats on playgrounds

We all know the story: In September 2002, an unidentified assailant or assailants began the first of apparently random killings in Greater Washington, D.C. As a chilling postscript to a rambling letter left at a shooting site, the unknown serial sniper added the ominous warning that “your children are not safe anywhere, at anytime.”

The string of murders and the media hoopla on its heels combined to provide a sense of doom, foreboding and terror throughout the area’s public and private schools. All related outdoor movements, from recess and playground activities to football games and soccer matches, were cancelled. One child had been shot at Benjamin Tasker Elementary School in Bowie, MD.

Educators and parents joined forces to protect the school children. Literally thousands of law enforcement officers, fire-rescue and military officials across four states and the District of Columbia joined forces in an unprecedented effort to track down and apprehend the perpetrator. By the time the killing spree was over, the serial sniper had taken the lives of ten victims and critically wounded three more.

“It has totally disrupted our family’s normal routine. However, it’s all the children, especially the very young ones, that I really feel for. It’s so hard to explain the situation to them. Yet, the older boys and girls have so much more to lose. It’s just an inconvenience for the little ones,” said Mrs. Mary Ellen Rogers, a wife, mother of three school age children and also a certified educator.

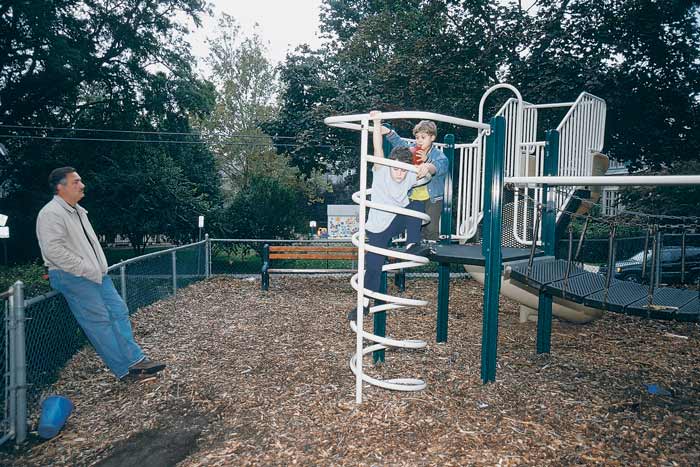

The Home Front. For many families, the sniper situation served as a catalyst for reflection, unity and discussion about their children’s safety in and out of school. Ghost Ground. On a Wednesday in early October, vacant lots like this one added another layer of apprehension to the sniper hunt and the concern for students’ safety.

Living in Bethesda, Montgomery County, MD, has given the Rogers family an all-too-close and personal experience of the terror that gripped the nation’s capital area. Playgrounds were devoid of all movement as recess and off-school-ground lunch activities were either canceled or moved indoors. Most schools in the area went to a “Code Blue” or emergency lockdown mode.

David and Mary Ellen Rogers and their three children—Emma, age 11, Alex, age 13, and Megan, age 16—are a very religious family. All Rogers children attend private schools. Many of their close neighbors have children in local public schools. The psychological effect of the sniper or snipers attacks on the community are the same.

Many “Tasker” parents kept their children home; attendance was down by one-third. Other parents served as volunteer guards, watching over nearby school street intersections. “Usually I’m embarrassed to walk around and hold my mom’s hand, but I don’t care today,” said Amanda Wiedmaier, a 13-year-old Tasker student.

At the Little People Preschool facility in Germantown, MD, Director Kris Small said that it has been an especially difficult time for their children. A brand new playground with a modern play structure was just about to open as the killings started. The educators elected to keep it closed until the tragic events were over. She said the children were extremely disappointed and could not understand why they could not go outside and use the play equipment.

So even in the grips of all this mayhem, how important is recess to a child’s development?

“Very important,” says fourth grade teacher, Colleen Malloy. “It is a break from the formal school day learning routine. This is when the children get to interact with other children in various different ways. It is a sharing period, a give and take, and game playing opportunity. It’s very important to a child’s physical and mental developmental process.”

Malloy noted that her students had “been doing pretty well,” thanks in part to a significant amount of rain during the school day. “They would normally have had indoor recess periods during that time, so the rain has been a definite bonus. If we get a string of nice sunny days from here on, I think it will become more problematic.”

(Another teacher, who opted not to be identified, added, “We’ve developed a saying around our school as far as our very young students go: ‘Pray for rain!’ At least that way the children would normally be inside and not clamoring to be outside on the playgrounds. It’s a sad state of affairs, but a true one.”)

Back in Business. Even in the waning days of the investigation and the arrest of two suspects, Washington-area parents and playground supervisors found themselves more attentive than ever to children’s outdoor activities.

Walking A Fine Line. In the midst of the attacks, Washington-area schools and daycare facilities had to improvise indoor play activities regardless of the weather.

The bulk of concerns regarding valuable play time centered on the younger children in grades K through 3, who have a morning recess and a lunch recess. “I think they are missing going outdoors much more…We can compensate with gym and other indoor activities, but I think the little ones need the ‘run around’ time.”

Here’s something to consider: Recess at all grade levels is very important to a child’s development, but with the older children they get to do it with sports. The younger children only get to do it on the playground. “Normally the young children can climb on play sets, jump rope, play kickball games and tag, use swings and slides,” Malloy told us. “It’s an important part of their day.”

For the younger children, teachers switch gears to work with them on motor skills development in the classrooms. The plain old run around time, however, is definitely missing. “Playtime is very important to take a child’s mind off the formal learning, some kind of a break is necessary to stimulate their brain in other ways,” continued Malloy.

And what about the teachers themselves? “One thing that we haven’t covered here so far is that this recess period is very important to the teachers, too,” she said. “They need the children to physically work out to burn off some of the pent up energy.”

Fellow educator, Ann Myers, noted that as teachers, “we’re frustrated and stressed, too. We simply must make the best of a tragic situation and pray for its resolution. We are all looking behind us to see what’s going to happen next. The children at this age simply do not fully understand what is going on. They only hear bits and pieces on the conversations. Unfortunately, they are at the age of imagination. Whatever they think is what is real to them.

Relief. Montgomery County police chief Charles Moose, flanked by federal agents, announces the capture of the two sniper suspects

No matter how you present the facts, children will take them a bit further as their imagination runs wild,” Myers added. “In other words, at this age, if one person has been shot, then five more people must have been shot. It was the same thing when the planes went into the World Trade Center buildings in New York. The children kept seeing the pictures and hearing the news. They felt that more planes were doing the same thing. And, unfortunately, we had the plane crash into the Pentagon here with all its casualties. When the kids hear it more than once, in their minds, they think that it’s happening over and over.”

Myers said she was doubtful that teachers would have been so frightened about the sniper if it had not been for the September 11th incidents. “But we can’t let that stand in the way of our obligation to the children to keep them as safe and reassured as we possibly can. We simply can’t move the playgrounds indoors, so we must make it as different as possible for them inside the school buildings. At recess now we open the doors to three connecting classrooms and a common room and allow the children to intermingle with each other.

The problems with such a situation—prolonged as it was—begin with the fact that kids still don’t have the freedom to run around and interact with other children and groups of children as they do outdoors. They don’t have the opportunities to make the friendships that will last them the rest of their school years and, in many cases, the rest of their lives. It is incumbent on us as teachers and parents, to do everything in our power to help them achieve this freedom under very difficult circumstances.”

Add new comment