Each one of us has something within that compels us to enter the delightful world of play. Walk by a playground, pause for a moment, and awaken your senses to see and hear the squeals of delight, the darting from one piece of equipment to another, the exuberance of winging high into the air, the arms stretched tightly overhead as children zip down the slide and then dash off to the next thrill. As adults and children, we play for a variety of reasons - to discover and explore, to test our abilities, to meet the challenge at hand, to release the burdens of the day, and to refresh our souls. Play is important for children because it helps them make sense of their world and their relationship to it. Children with disabilities are no exception.

According to the Kellogg Foundation's Able to Play Series, nationally about one in ten children (over 6 million) has a disability that inhibits their use of a traditional playground. Fortunately, guidelines from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) are in effect to "regulate that all new and altered play areas will be accessible to children with disabilities." These regulations require that playground designers and builders meet certain specifications in order to be accessible. Beyond compliance to the rules, what is the basis of the importance of accessibility? The essence is in the difference it makes in the life of each child who is touched by the joys of being able to play alongside his peers.

Being left on the sidelines in play has a great effect on how we view ourselves and others.

Accessible playgrounds enhance the social experiences for children of all abilities. Think back on our own childhood. Were you the last one to be chosen when playing softball at recess or in the neighbor's yard? Can you remember wanting to try a new activity but circumstances prevented you from doing so? If your answer is affirmative, perhaps you've personally experienced exclusion and still have vivid memories of how that felt.

When barrier are removed and a child is able to contribute to play, they are valued by their peers, which ultimately translate into their own self-esteem. If kids Iearns to appreciate each other's strengths and diversities, they are more apt to develop socially satisfying relationship so that all the children involved are recipients of the benefits.

Modifications can bring children together during playtime. For example, at Siskin Children's Institute socialization is encouraged in the sand box by using corner chairs, which support a child who otherwise would not be an independent sitter. These special chairs allow children in wheel chairs to sit at the level of their peers and play side-by-side.

Accessible playgrounds provide avenues for enhanced physical development. Modifying play equipment to include children of all abilities and allow them to participate in large motor movements, sensory and vestibular experiences will help them develop balance, strength and mastery of gross motor skills. One philosophy in development is "We learn to move and move to learn." The opportunities to hop, run, jump and swing aid physical development and perfect muscular coordination.

Play should be pleasurable, and incorporating therapy into the process should not interrupt the fun. For example, at Siskin Children's Institute, occupational, physical and speech therapists are routinely found on the accessible playground, incorporating integrated therapy into the play experience. Lisa Battersby, physical therapy assistant, stresses that variety is a key part of the process because you have to vary the experience to make play interesting, creative and fun for the child; otherwise, it would be work!

This is true for previous student Grant Hudson, who graduated from Siskin Children's Institute in 2006. The hill on the lnstitute's playground was used as a continuation of his physical therapy, allowing him to walk uphill and downhill while he was "mowing the grass."

Doris Bergen, professor of educational psychology, in a paper presented at the American Educational Research Association states: "Play (not work) should be the major focus for play activities. Because of their (the adults) concern for the child, play activities can become work activities in the interest of intervention and remediation. Play for at-risk children should have the same purposes as for children who are not at risk and do not have a disability." If play is too difficult (which often occurs on a typical playground for a child with a disability), motivation will cease. The child needs to be successful at some point during play in order to stay engaged and motivated.

Accessible playgrounds provide avenues for enhancement of varying developmental tasks. In addition to physical development and socialization, activities on play equipment can help children of all abilities gain "real world" understanding of concepts like over, under, through, fast and up. In addition, certain movement activities stimulate the brain's language centers, facilitating development of language skills.

For many children with disabilities, sensory issues affect their everyday lives. Battersby consistently seeks ways to work with children who have limited movement experiences and special sensory needs. They have become observers of their environments rather than participants. The swing area on the playground can have great impact on the child's sensory experience and give him the opportunity to be a participant.

It satisfies the need of movement for children with varying diagnoses.

Children with autism, for example, often crave movement. Conversely, children with cerebral palsy (and other diagnoses causing limited mobility) are sometimes fearful of movement and rarely experience free movement. According to Amy Thomas, occupational therapist at Siskin Children's Institute, "Movement activates the vestibular system, which is responsible for developing balance skills, motor planning activities and general awareness of where your body is in space. Children of all abilities should have daily opportunities to experience a wide variety of movement activities."

The hill, as previously mentioned, also offers an opportunity for sensory experience. It was included in the playground design at Siskin Children's Institute and has become one of the most popular areas of play. It is great for exploration, is not as predictable as a flat surface and has several textures which offer varied sensory experiences.

Children who use wheelchairs often view the world from a single line of sight.

Involving children in new situations to give them different perspectives can be beneficial. For them it is difficult to climb a tree and look down or crawl under an object to peer upward. They see life from a "monotone position." When a child can be placed on his/her back and gaze up through the trees into the sky, the world is viewed from a totally new perspective. When ramps are built so that wheelchairs can transport those children to various levels of height, what a thrill it is to be able to look down on something that is normally seen from the sides!

The adult facilitator is a key factor in each child getting the most from an accessible playground experience. Siskin Children's lnstitute's Related Services Coordinator, Paula Offutt, states, "Just because it's accessible doesn't mean every child will utilize it." Many children may not know how to play or may not feel comfortable on the playground. When an adult facilitates play, without ordering or interrupting, the child can have a meaningful experience.

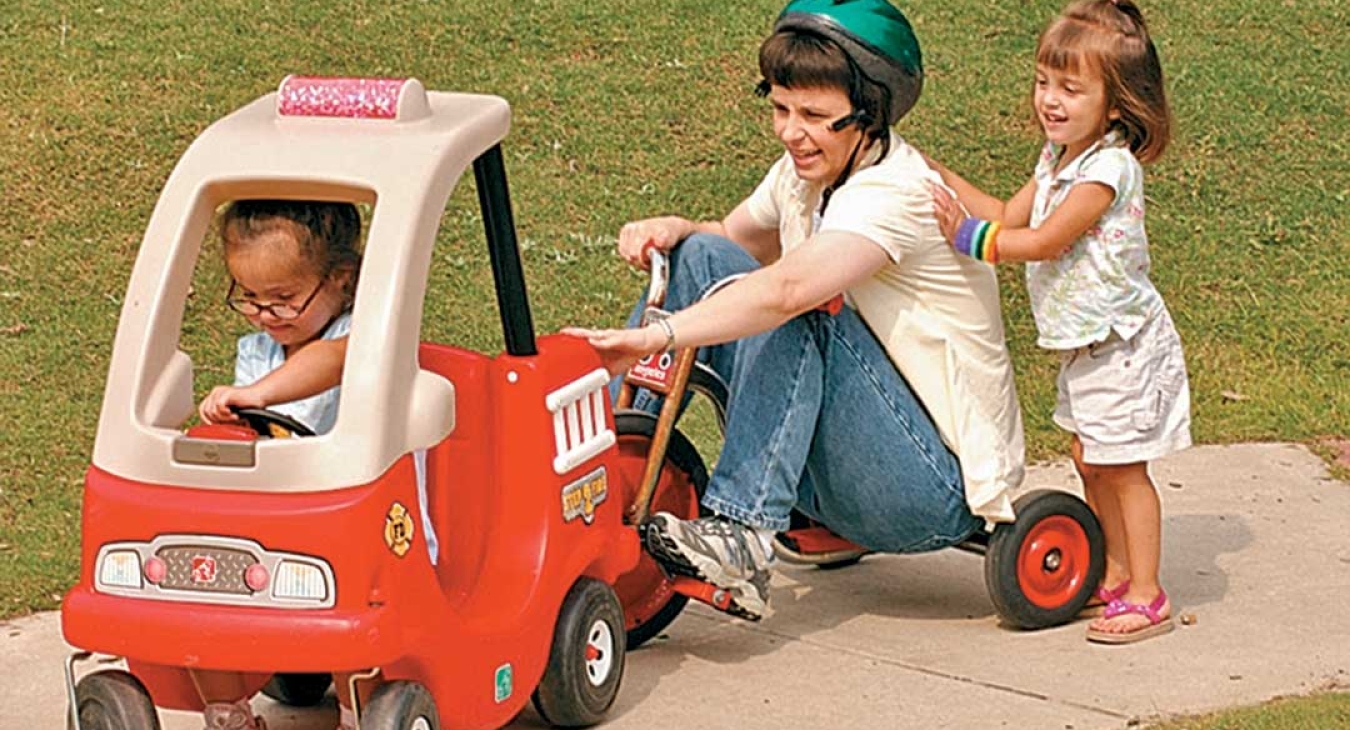

Individuals of all abilities and all ages can benefit from accessible playgrounds. Parents often speak of making their own "modifications" to accommodate their child on a typical playground. When an accessible play space is available, the parents don't have to worry about accommodation, and they find it much easier to transfer or lift their children onto the various structures. The burden is lifted emotionally and physically. Even adults in wheelchairs can access many of the play areas and be closer to the child at play.

Although specific modifications are present in an accessible playground, it is still recognized as a vibrant and inviting area to children of all abilities. No fun is lost for the typical children. Jean Schappet, co-founder of Boundless Playgrounds, notes in High Expectations, "When we built playgrounds that were good for children with disabilities, the equipment was better for all children."

It is rewarding to see children of all abilities and backgrounds play together, benefiting from and enjoying one another. Similarities and differences abound, but through shared play experiences children can learn confidence and acceptance while developing healthy self-esteem. However, through a child's eyes simply having fun is the key. All kids just want to have fun!

About Siskin Children's Institute

Located in downtown Chattanooga, Tenn., Siskin Children's Institute is a leader in serving children with special needs, their families, and the professionals who touch their lives. Each year, the Institute serves more than 100 children through Siskin School, a unique educational environment for children of all abilities. The institute also offers a variety of community outreach programs through the Siskin Training and Resource Center including playground education to help individuals and organizations create barrier-free playgrounds for children of all abilities.