"Playground” is a generic term, sometimes referring to any place where people play—indoors or outdoors, natural or built. Contemporary usage of the term usually refers to a place set aside and developed specifically for children’s play using manufactured play equipment, as seen in schoolyards, parks, child care centers, fast food restaurants, and backyards.

Historically, such playgrounds are new in America, having appeared as late as the mid-1800s with the introduction of indoor gymnastic equipment inspired by the German physical fitness emphasis. Fabricated playgrounds never gained a firm foothold in this country until the early 20th Century with the rise of the playground movement and the introduction of traditional manufactured play equipment such as swings, merry-go-rounds, jungle gyms, and giant strides.

"I never teach my pupils; I only attempt to provide the conditions in which they can learn." Albert Einstein

Before that time children played in the hills, creeks, and farmyards of rural areas and the streets and vacant lots of towns and villages. For centuries the natural wilderness was the main playground for children. This presented playgrounds that were challenging and posed hazards. However, coupled with the ever-present work demands for most children they were remarkably effective in producing active, creative, street or country-wise children with strong bodies and sharp intellects—exemplified by such groups as Native American children, immigrant children of the American frontier, and children of the Depression.

During the last quarter of the 20th Century, an unprecedented shift was seen in the play and playgrounds of American children. Play in traditional outdoor playgrounds, natural and fabricated, began to be overshadowed by sedentary, indoor electronic play, organized sports, and parental fear of strangers—all contributing to a decline in outdoor play. Recess and spontaneous outdoor play at school succumbed to competition from high-stakes testing, standardized curricula, fear of lawsuits, and efforts to sanitize play—no dodgeball, no chase games, no body contact or running on the playground, and no hugging (see Frost, 2007).

With the demise of active outdoor play and recess, children developed health problems at an alarming rate—obesity, circulatory abnormalities, depression, and symptoms of other disorders. The consequences of such rapid-fire assaults on the play of children were astonishing but predictable. Throughout recorded history, eminent philosophers spoke to the values of children’s free, spontaneous play, and research throughout the 20th Century confirmed its value and addressed the consequences of not playing. Now professionals concerned with the welfare of children are engaged in widespread reexamination of probable causes and searches for solutions to this emerging health crisis. Just as there are differences among professionals regarding the appropriate roles of play in rearing and educating children, there are also differences regarding the merits of different types of environments and materials for their play.

Children at all skill levels beyond toddlerhood are generally more adept in searching out play places and play objects that meet their abilities and needs than are adults, and healthy children are remarkably creative in bending the environment to their will and play. Despite such astonishing abilities, children are given precious little say-so in creating their playgrounds. We can learn more about what many school-age children really want and need in their playgrounds by asking them and watching them play rather than from adults talking among themselves. One of the few organized playground groups that seem to understand this are those who train and serve as play leaders on European adventure playgrounds and city farms.

From a developmental perspective, the play needs to be addressed on playgrounds are simply stated as those elements that respond to the forms or types of play characteristic of those who will play there. Beginning in early infancy, children begin to play—at first exploring via their built-in sensory mechanisms and reflexive wiring. As neurons multiply at an astonishing rate and cognitive, social, and physical skills develop, exploration, imitation, and imagination lead to the first signs of genuine play. This early form of play, often referred to as exercise or practice play, does indeed qualify as exercise. It also gains force through repeating actions over and over. A good example of this would be a toddler awkwardly throwing or kicking a ball and doing it over and over as an attentive adult hands it back for yet another kick.

Such patterns quickly lead to variations of the theme and the miracle of beginning pretend play follows closely behind. These primitive beginnings are coupled with growth in equally fundamental elements of physical, social, and intellectual skills, but progress is dependent upon continuing stimulation, play materials, adult support, and opportunities to play. These are all requirements for healthy development that will continue unabated throughout childhood.

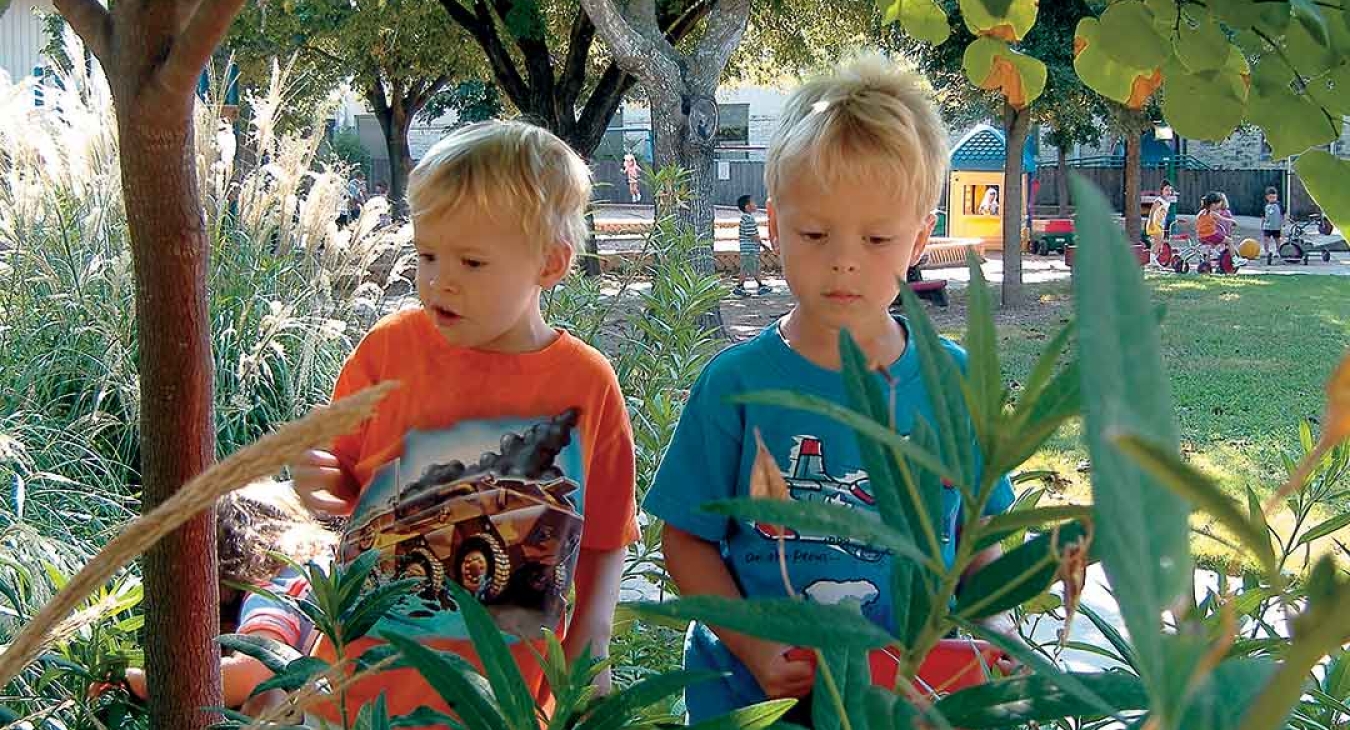

By age two or three, the play of healthy children progresses into extensive make-believe or pretend play wherein they mimic the roles of adults and almost any event they hear or see. They are also gaining skills in construction play—stacking, sorting, and building with small blocks, rocks, or almost any small objects. Sand and water, already among their most adaptive play materials, will not lose their appeal and their developmental and restorative powers for many years. Gross motor skills are developing rapidly and are promoted with built-to-scale climbers, slides, swings, bouncing devices, tricycles, and other wheeled vehicles. Enclosures for house and store play complement these play elements.

Children’s early child development center playgrounds and play centers are located both indoors and outdoors for the core of good early programs is play. Yes, play, no excuses, no regimented shortcuts—just lots of interesting materials bought, begged, created, natural or fabricated, and supportive adults who know how to complement free, spontaneous outdoor play with indoor music, art, drama, storytelling, and other creative arts.

Play does not steal from academics or success in school. During the years preceding entry to formal school, play and playgrounds are the fundamental keys to developing those basic pre-concepts essential for later academic success. For our youngest children, play is the curriculum, and playgrounds (indoors and outdoors) are their classrooms.

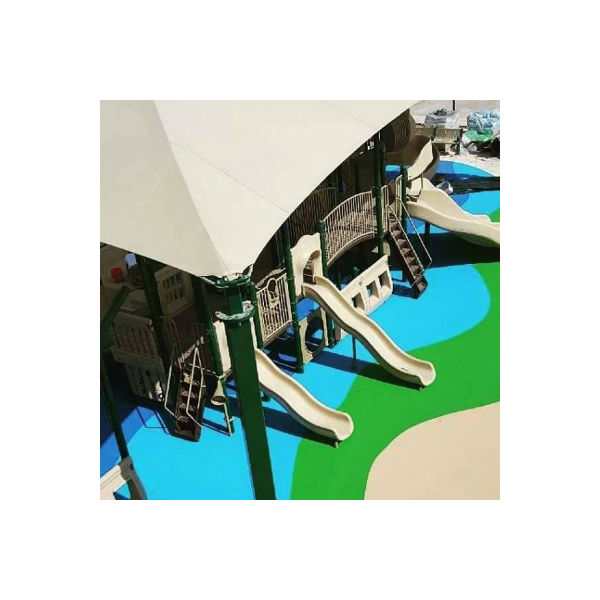

By entry to kindergarten, good playgrounds have evolved to meet the rapidly expanding play repertoires of the children. Whether in the backyard or in the school, there should be space for organized games, spaces for make-believe, spaces for planting and tending plants, raw materials for games, and stuff for creating dens and houses. Every good outdoor playground in limited spaces must have storage for loose parts (the tools of play), which are essential to children’s natural tendencies to explore, construct with tools, create play themes, and interact with peers—in short, to learn and grow.

There is no need for a “playground curriculum.” All healthy primates are genetically wired to play, and excessive adult interference short-circuits the process. As children grow toward adolescence, their play preferences and needs continue to change; and consequently, their playgrounds take on a new look. Since risk is essential for developing safety consciousness and motor skills required to master challenges, structures for exercise play are gradually expanded and made more challenging. Spaces for centuries-old traditional games such as four-square and kickball must also be available.

Contrary to popular opinion, traditional chase, dodgeball, tag games, and rough-and-tumble play contribute to healthy development and help prepare children for playing safely. Fabricated play structures, properly designed to enhance hiding and flow, lend themselves to such play—if adult supervisors aren’t too squeamish or dainty to allow such delightful enterprise. Adults must reject the growing trend toward sanitizing play and allow ever-increasing physical and mental challenges that are popular, beneficial, and “socializing” for both boys and girls. Standardization and excessive regulation of curricula and playgrounds, excessive safety rules, and denying recess to children conspire to diminish play—exacting a heavy toll on children’s health and development.

References

- Frost, J. L. (2007). Genesis and evolution of American play and playgrounds. In Sluss, D.

- J., & Jarrett, O. S. Investigating play in the 21st century. New York: University Press of America.