Have you ever driven by a beautiful new playground and thought “That looks really good. I wonder who made the equipment, and who supplied the surfacing?”

It’s easy to forget that the second part of the question, “Who supplied the surfacing?” would, not so long ago, probably have sounded silly. That’s because, with the exception of molded rubber tile used in a few large cities and a limited amount of loose recycled tire rubber, playground surfacing was a local affair. Someone put in the playground equipment, found a nearby source of wood chips, sand, or gravel, and spread it on the playground.

The 1980s: Beginnings

This changed in the mid-1980s when a group of forward-thinking innovators saw the need for better surfacing and set about developing products to meet this need. They included Robert Heath, the founder of Fibar LLC, who realized that the fibrous wood particles that Fibar was selling to cushion the impact of thoroughbred horses’ hooves could also cushion impacts from playground falls. And David Brantley, founder of No Fault Sport Group, who figured that the polyurethane/rubber surface he was installing on tennis courts and running tracks could, with an additional cushion layer, serve as the resilient, easily maintained safety surface sought by owners of quick service restaurants for their play centers. And the originators of ECORE International’s PlayGuard safety tile, who recognized that the bonded recycled rubber tile installed on playgrounds throughout Europe would work equally well on playgrounds in North America.

These innovators began what, at the time, was a novel concept: surfacing material designed and sold specifically for use as a resilient surface under and around playground equipment. In other words, “commercial playground surfacing.” As with any new concept or innovation, there was much resistance in the early days. “Buy surfacing for my playground? I get wood chips for free from the local recycling center!” Or worse, “Resilient surfacing for playgrounds? I grew up playing on asphalt, and I’m none the worse for it!”

However, commercial playground surfacing suppliers persevered, and playground designers and operators slowly began to embrace the concept. Then in the late ’80s and early ’90s a series of events occurred which changed how people thought about playground surfacing and catapulted commercial playground surfacing to prominence.

The 1990s: Surfacing Comes of Age

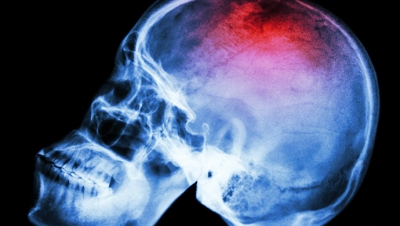

In December 1989, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission’s (CPSC) Directorate for Epidemiology published a study (Playground Equipment-Related Injuries Involving Falls to the Surface, by Deborah Kale Tinsworth and John T. Kramer) which found that falls from playground equipment to the surface below accounted for 60% of all injuries reported. The fact that playground surfacing was a factor in more than half of all playground injuries made surfacing a major playground safety issue and an important consideration when designing a playground.

In November of 1991 the Consumer Product Safety Commission published a revised version of The Handbook for Public Playground Safety, defining the critical height of a playground surface as the height below which a life-threatening head injury from a fall to the surface would not be likely to occur. The performance-related definition of critical height, according to the CPSC and ASTM International (ASTM) F1292, the industry standard containing the test method to determine critical height also published in 2001, was the maximum height from which an instrumented headform can be dropped without exceeding a peak deceleration (Gmax) of 200 and a HIC (a measure of deceleration over time) of 1000 upon impact. Thus in the space of less than 2 years:

- falls to the surface were found to be the leading cause of playground injuries,

- the CPSC defined a measurable threshold (critical height) for life threatening head injuries, and

- a test method to determine the critical height was published.

Now the 1991 Handbook also contained a table showing the critical heights of commonly used surfaces like wood mulch, bark mulch, sand, and gravel, which could be sourced locally. However, and here’s the rub, how could a playground operator be sure that the mulch, sand, or gravel installed on their playground was exactly the same as that tested by the CPSC? The answer, of course, is that they couldn’t.

Commercial playground surfacing suppliers, on the other hand, could provide laboratory test results documenting that the surface that they were supplying, and which was installed on the playground, met the CPSC and ASTM critical height requirements. Talk about peace of mind! Commercial playground surfacing was off and running!

The 1990s were a boom time for commercial playground surfacing (as well as commercial playground equipment) as playground owners replaced obsolete and unsafe equipment and surfacing with the new surfacing almost invariably of the commercial variety.

Engineered wood fiber (EWF), as the fibrous wood particles sold by Fibar and other suppliers came to be known, covered most North American playgrounds by the end of the decade. Poured-in-place (PIP) surfacing expanded from quick service restaurant playgrounds to amusement parks, family entertainment centers, and park and school playgrounds. Bonded rubber crumb (BRC) tile was installed on big city playgrounds throughout the country.

Dozens of new commercial surfacing suppliers entered the business, giving playground designers and operators not only a multitude of surfacing choices but of suppliers as well.

Innovation also continued at a brisk pace. EWF suppliers introduced new underlay systems using drain strips, rather than gravel, for more effective and economical drainage. PIP companies added a variety of bright new colors and offered improved color stability. BRC tile producers also introduced vibrant colored top surfaces as well as mechanical fastening systems that reduced or eliminated the need for adhesives and allowed installation over different sub-bases.

2000-2010: New Challenges, New Surfaces

Shortly after the turn of the century, in 2001, the federal government threw US playgrounds a bit of a curve.

Those involved with playgrounds had long been aware that the Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, which was made law in 1990, affected most playgrounds as they are public facilities. However, how the ADA affected playgrounds was not clear. In November of 2001 the U.S. Access Board, the federal agency tasked with promoting accessibility, placed the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) for Play Areas in the Federal Register. The guidelines also became effective in November of 2001.

In addition to guidelines for play equipment, ADAAG for Play Areas also contained guidelines for playground surfacing. These guidelines, which address the “accessible route” from the playground entrance to the play equipment and between play events, contained requirements for slope, changes in level, and width. Most importantly, however, ground surfaces along the accessible route were required to comply with ASTM F1951.

ASTM F1951 Standard Specification for Determination of Accessibility of Surface Systems Under and Around Playground Equipment uses an instrumented wheelchair to determine the work required to propel the wheelchair across the surface being tested. This work is then compared with the work required to propel the wheelchair up a smooth, hard 1:14 ramp. If the work to traverse the surface is less than that required to go up the ramp, the surface passes F1951.

So, as of 2001, one federal agency (the CPSC) was recommending that playground surfaces be resilient, and another federal agency (the Access Board) was recommending that playground surfaces be the opposite, firm and stable. Who said being a playground surfacing supplier was easy?

However, commercial playground surfacing suppliers rose to this new challenge. Engineered wood fiber suppliers determined that, with proper compaction, EWF met the requirements of ASTM F1951. EWF suppliers also added wear mats to their product lines, recommending the use of these mats in high wear areas to prevent displacement of wood fiber and thus maintaining accessibility.

Poured-in-place and BRC rubber tile playground surfaces passed ASTM F1951 with flying colors, their top wear surfaces offering little rolling resistance to wheelchairs. (Their lower density bottom layers provided the necessary resilience to meet CPSC shock attenuation guidelines.)

However, for non-commercial playground surfaces like wood chips, wood mulch, sand, and gravel (i.e. those shown in the CPSC Handbook table), the ADAAG Play Area guidelines were the final blow. None of these surfaces, with the possible exception of some types of wood chips, meet ASTM F1951, and thus are not viable options for accessible playgrounds. (Sand, however, is still often used in non-accessible play areas because of its play value.)

The new ADA requirements for playground surface accessibility thus provided another boost for commercial playground surfacing.

The use of commercial playground surfaces continued to grow during the first decade of the new millennium, albeit at a slower pace, as much of the obsolete and unsafe surfacing (and playground equipment) in place in the past had now been replaced. This period also saw the entry of several important new players into the commercial surfacing arena.

Rubber nuggets or chips derived from tire recycling had been offered as playground surfaces since the 1970s. However, these black, sometimes dirty (or perceived dirty) products found limited acceptance among playground operators. Then, in the late 1990s, a clever Ohio chemist found a way to coat the rubber particles with colored pigments and, voilà, colored loose-fill rubber playground surfacing (aka rubber mulch) was born. The coloration technique spread rapidly and a number of rubber recyclers soon were supplying the product.

The black ugly duckling had become a brightly colored swan! By the middle of the decade, colored rubber playground mulch was going strong. Not only did the product look nice, but it was also resistant to deterioration and offered some of the best shock attenuation available, combining the resilience of rubber with the impact-absorbing properties of a loose-fill surface (due to air voids and displacement on impact). While not nearly as popular as engineered wood fiber, rubber mulch offered buyers another loose-fill option for their playgrounds.

The first commercial playground surfaces (i.e. EWF and PIP) came about when suppliers of these surfaces for other applications realized that these surfaces could also be used on playgrounds. This was the case with another playground surface that rose to prominence in the last decade - artificial turf or artificial grass playground surfaces. Artificial turf has, of course, long been used on sports fields. So, several turf suppliers reasoned, why not on playgrounds?

Synthetic playground grass uses the same basic design as that for sports fields – sheets of synthetic turf installed over an impact-absorbing pad and stabilized by a particulate in-fill, with shock attenuation and turf properties appropriate for playground applications. The product offers many of the advantages of unitary rubber surfaces: resilience, low maintenance, and good accessibility. The turf top surface fits well with the trend to nature-themed playgrounds. The comfortable surface is an advantage for playgrounds used by younger children.

As a result, artificial grass playgrounds have grown steadily since their introduction in the early 2000s and have become an important unitary commercial playground surface, although much less widely used than poured-in-place surfacing.

2011-2015: Playground Surfacing Today

Choosing a surface for one’s playground in 2015 is a far different experience than that of 25 years ago. Instead of heading for the local wood waste recycling facility, landscaping materials center, or building supply dealer to pick up whatever might be available, purchasers are now apt to sit down with a landscape architect or playground equipment and surfacing sales representative to discuss their surfacing needs and the many options available to them. More complicated, sure, but the result is also likely to be much more satisfying.

The many playground surfacing choices discussed in this article are all available to today’s buyer, each with its own distinct advantages and drawbacks, as well as numerous suppliers for each type of surface.

All commercial playground surfaces have undergone sophisticated testing for shock attenuation and accessibility, with laboratory results available to the customer documenting compliance with relevant safety and accessibility guidelines and standards. There are also product-related ASTM standards for engineered wood fiber and loose-fill rubber, with one for PIP in the works, specifying requirements for composition, purity, and suitability for use on children’s playgrounds. Furthermore, many suppliers participate in an industry certification program, administered by the International Play Equipment Manufacturers Association (IPEMA), providing independent laboratory certification that their products meet relevant ASTM standards.

While some purists may grouse that playgrounds and playground surfacing have been ruined by bureaucrats and businessmen, it’s hard to argue that today’s playground surfaces are not safer, more accessible, and more reliable than in the days of throwing down whatever was available and hoping for the best.

The remarkable innovation that has characterized commercial playground surfacing continues apace with new, more durable polymeric wear surfaces for PIP and BRC tile; topcoats with customized designs, logos, and figures offered on those products; urethane-bonded EWF surfaces offering additional firmness and stability; and more reliable and long lasting installation systems and techniques offered for BRC tile.

And new playground surfaces continue to be introduced, the latest of which are the so called “hybrid surfaces,” which feature a loose-fill rubber base covered with polymeric or turf sheet material. These surfaces are said to offer the resiliency of a loose-fill product combined with the accessibility of a unitary surface. Hybrid surfaces are in their infancy, so time will tell how well they are accepted. However, the concept certainly is intriguing.

The bottom line is, that as we drive by newly installed playgrounds in the future, the surfacing will still probably give us plenty to talk about!

Need consultation on our playground meeting ASTM

Please email me at [email protected] and give me a number to call and timeframe to discuss my Subject

New location

Hi I'm opening a new location of child day care center and will need to cover my playground please contact me as soon as possible

(516)903-9299

Health Risks of Rubber Playgrounds

We need to seriously look at the health risks our youngest citizens face when playing on material made from petroleum based rubber tires. Recycled doesn't mean clean. No one seems to want to address this here.

Centerburg Schools

We are interested in getting our local schools playground looked into. They've got down non-costed recycled tires on the playground that is staining pur kids shoes & clothes BAD! Lord only knows what the kids are breathing in.

In reply to Health Risks of Rubber Playgrounds by Concerned Mom … (not verified)

Thanks for sharing such a…

Thanks for sharing such a valuable post with us. I am gonna bookmark this site.I have also seen your post it is awesome!

Add new comment