Sufacing needs regular maintenance

We all know the 2010 Standards for Accessible Design requires frequent and regular inspection and maintenance of playground surfaces. But what does regular mean? What does frequent mean? What does maintenance mean? Here are some stories from our work in the evaluation of thousands of playgrounds for compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and some pointers for playground owners, operators, and users.

IS YOUR ACCESS SURFACE MAINTENANCE UP TO THE TEST?

Is it money, or lack thereof?

Is it a failure to understand the requirements?

Are the requirements too stringent?

Do we need some new innovative surface on the market?

Is it some combination of all four?

That’s what we wonder when we see some playground surfaces. Our industry has known for decades the importance of properly installing playground surfaces, and even more importantly, regularly maintaining those surfaces. In the ’90s, playground accessibility for children and adults with mobility impairments was an emerging idea and not a necessarily welcomed idea at that. But as we say that, we also note that we see many agencies, large and small, with a superior commitment to and understanding of playground surface access. Why aren’t the lessons learned at those agencies followed elsewhere?

This brief article takes a peek at some of the surface maintenance issues we have seen.

The Parks Superintendent

In a mid-sized city we scheduled a meeting with the parks superintendent, department planners, the deputy director, and the risk manager. Meeting at a playground with an engineered wood fiber surface, the whole point of the meeting was to discuss maintenance and develop a strategy for how often “regular and frequent inspection and maintenance” should occur. We could have had a great meeting without the risk manager. We could have gotten by without the planner, who was really more interested in new sites. We wanted the power of the office of deputy director, but also could have had a great meeting without the deputy director.

But the one person indispensable to the discussion was the parks superintendent, who controlled the parks staff. And the parks superintendent didn’t show, didn’t call, didn’t answer our calls, and was too busy to meet the rest of the week.

I have thought about this a lot and believe his absence was caused by several complex factors. First, it was a message: he doesn’t think “this access thing” is important, and does not want to change the way things have been done. Second, he also knows it is unlikely he’ll get more maintenance staff for an increased maintenance charge, so the meeting had no benefit to him. Third, he wants the new resources needed to properly maintain surfaces but believes he’ll only get new resources if the agency is embarrassed.

We See…

Our firm helps states, counties, cities, park districts, and school districts comply with the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). We have clients in coastal states, plains states, desert states, mountain states, and every other state, including the state of denial. In our work, we see playground surfaces that lack evidence of maintenance. Some look like the picture below, where weeds growing in the surface is never a winning look.

We understand that assigning a crew to a playground on a daily basis is not likely to occur. But this playground hasn’t been tended in a week. Plants growing in the impact attenuating surface is a sure indicator that the surface is not frequently inspected and regularly maintained.

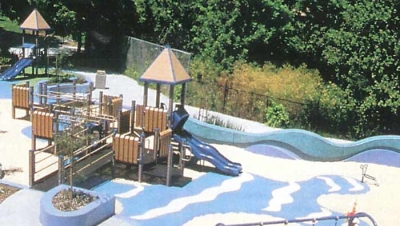

Other playground surfaces have that horrible mix of safety flaws and access flaws. The picture below is a good (bad?) example.

Other safety and access maintenance interface problems include EWF or sand that is kicked up onto the rubber mats or PIP, degrading the rubber. Related to low fill of EWF, we often see significant changes in level between loose fill surfaces and rubber surfaces, making the loose fill impossible to navigate. There are still other problems here…exposed fabric included.

One of our greatest concerns is the intermixing of EWF with “wood chip” or mulch. That is an absolute failure by the maintenance staff.

Surface Access Deficits and Play Components

Another issue is the relationship between the surface and the elevated play components. We consistently see, and so do most readers, loose fill EWF that isn’t at the appropriate levels. Let’s disregard the safety issue for a moment. That instantly means that the height of the transfer system, by far the most frequently used means of access to elevated play components, is out of the range of 11” to 18” above the surface, and closer to 21” to 24” above the surface.

In other words, unusable by a child in a mobility device.

Finally, What is the Test?

This isn’t a trick question. Do agencies maintain playground surfaces to ASTM F1292? Of course that’s the effort. But how many are maintaining playground surfaces to ASTM F1951? We see four key elements: Add EWF as necessary, level, wet, and compact.

- Replenish kicked out EWF (every agency does this)

- Rake and level the surface (many, but not all do this)

- Wet the surface (we can count on one hand the number of agencies that we know of that wet replenished EWF)

- Compact the replenished, raked and levelled, and wetted surface (we can count on one hand the number of agencies that we know of that compact wetted replenished EWF)

Those four tasks are a critical test. Those steps assure your maintenance plan will meet the F1951 requirement and the 2010 Standards requirements.

The most important test though is use. Do children with impaired mobility use this surface? Do parents who use mobility devices use this surface?

The Future

We need a different way of viewing surface, and we need different surfaces. As long as agencies feel they are being dragged into compliance, the lack of truly accessible and safe playground surfaces will continue. The manufacturer that wins this race will also win every RFP and every bid.

Source