Inquiry-learning

A recent conversation with Michael Haran caught my attention when he used the term “inquiry-learning.” He defined the term as not only discovering the world around the learner but also looking for the serendipitous. He explained that this sort of thinking is what scientist and engineers do; not just solve the problem or prove the theorem, but to seek the exception as well.

As I considered his idea I realized that the same trait is true of artists and designers. I know in my own experience that the “work” I’m engaged in is just the canvas on which I find the unexpected, which is where the real treasures lie. Indeed, this quality is generally true of any creative person regardless of the discipline.

I have written previously about what I refer to as the “learning spectrum” that starts with discovery, leading to play, then practice, and finally mastery. Thinking about Michael’s idea I had to consider that perhaps the term “discovery” should be changed to “inquiry.” However, further reflection led me to realize that play and inquiry are just two words for the same phenomena.

Here’s an example. Consider the toddler’s first attempts to use a spoon. There are many basic skills that have to be mastered to be able to transport food from the dish to the mouth, but once accomplished, is the child done learning? Hardly. Now that he has “discovered” what the spoon can do in its normal function, he explores its uses as a pea catapult, a nose decoration, and even a percussion instrument.

Transforming our Ideas about Play and Learning

Recently I have become the Curator for Now Playing Worldwide, a PBS series in early development. My function is to search as broadly as I can to find experts and information that will support and inform the series. In that capacity I have been virtually overwhelmed by stories of the radical change taking place all over the world. Whether you call it play, child initiated or inquiry learning, this is a revolution in the making.

These days the most valuable commodity out there is creativity. Whether you count the value in dollars or solutions to tough problems, people all over the globe have come to understand the transformative and disruptive power of playful engagement. Kids light up; they get excited about school and learning. Playful professional environments and employees are responsible for many of the most important innovations of our time.

To create an environment for play learning it is not enough, or even correct, to just put the child in charge. Play-based and inquiry-based learning still requires a lot of adult participation and guidance. Indeed, the teachers with whom I collaborate tell me that in many ways inquiry learning is even more demanding than teacher-directed education, because they spend most of their time observing and have to know the right moment to step in with new materials or suggestions.

Children’s Way of Knowing

I recently came across the work of David Ramsey and his paper Play and Children’s Way of Knowing. The clarity of his exposition really helped me see that the majority of what we adults do when designing for play has little to do with what children seek and is for the most part about what adults expect. For example, adults want order and neatness while kids want complexity and the ability to manipulate elements in the environment.

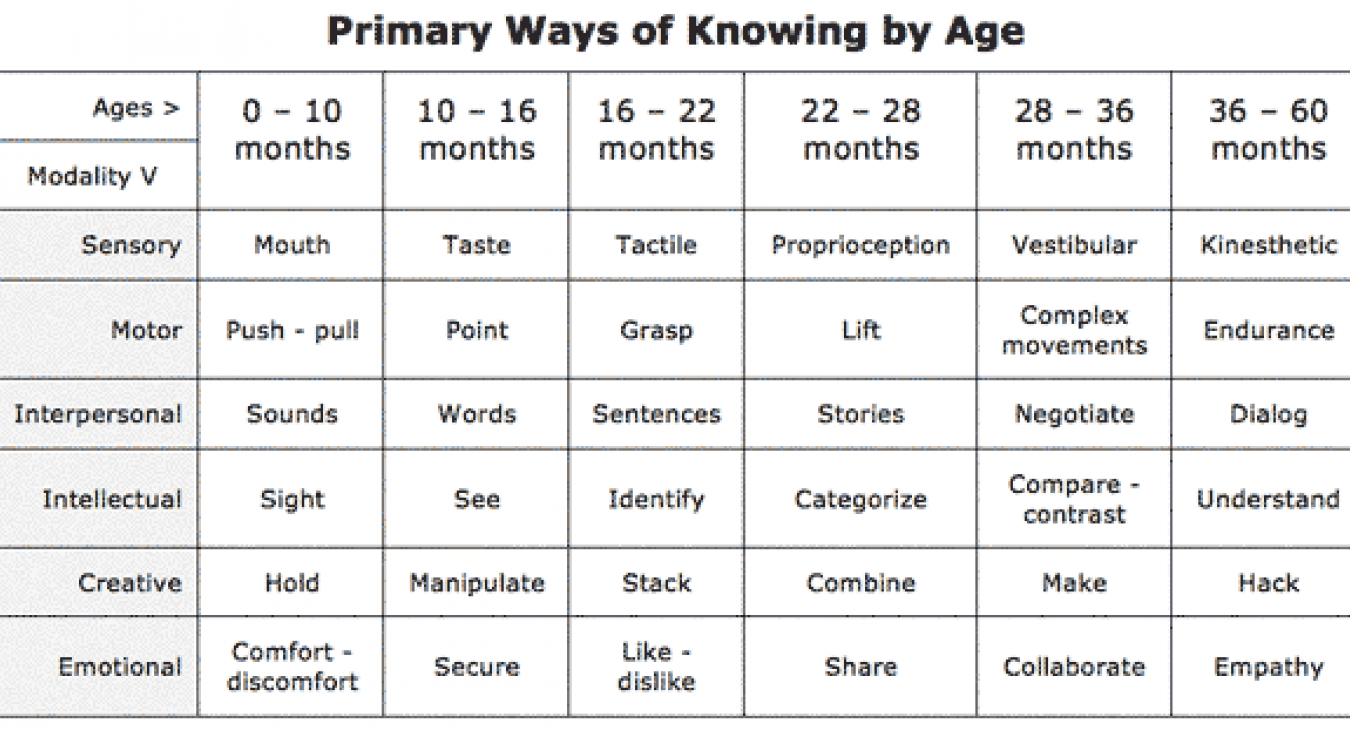

For the children to become fully engaged and receive maximum benefits, the environment needs to match their way of knowing at each developmental level. As children grow, they use different modalities and capabilities to explore and get to know the world about them. This means that they seek, respond to, and benefit from environments that maximize the opportunities to use their primary investigative methods at each stage of their development.

Primary perceptual modality for adults is intellectual. They seek spaces that are orderly, functional, non-threatening, and predictable. Unfortunately, environments created for children generally must conform to these adult expectations before they include features that are age appropriate for children. In addition adults rarely, if ever, provide for the complete range of developmental stages; for example, adult-designed play spaces that are primarily composed of motor and vestibular challenges assume that this will meet the needs of all ages. Today’s typical playground does a fair job of supporting motor development but only accommodates the other developmental modalities, if at all, by accident.

To illustrate this idea I have created a chart that is useful when designing from the learner’s needs rather than the adult’s expectations. I share this with the caveat that any chart of ages and stages may be a useful conceptual tool but does not, and cannot, accurately encapsulate the reality of childhood during which any modality may be expressed at any age. The chart depicts trends, not the truth.

Primary Ways of Knowing by Age

Let’s see how the chart can be used to inform design, in this case, a play area for ages 3 years and up. We will start with a combination of bouldering rocks and challenge courses like those created by UPC Parks. The reason for this choice of play elements over standard play apparatus is that every kid knows, from his or her first glimpse of the challenge course, that this environment will be really exciting for their whole body and it’s not just “little kids’ stuff.”

To be able to meet all of the ways this group engages in inquiry learning through play we will need to go beyond a typical installation of rocks or ropes in several ways. To meet the motor/endurance criteria we will want a really big environment with lots of complexity and diversity, not just a couple of ropes from a play structure to a rock.

In all mountaineering, the interpersonal/dialog aspect is core to the sport. Climbers talk all the time, be it about the best way to accomplish the climb or just about lunch. To develop the solution to what is known in the sport as the “problem,” or for the most difficult problem, the “crux,” a lot of specific moves are proposed, considered, and strung together to make the “route.” To be successful at this the climber has to be smart, an excellent communicator, and bring good judgment to the task.

To satisfy the creative element we need to provide a way for the kids to hack the course. The best way to do this is to allow the climbers to “tape” their route, i.e. use small colored stick-on dots to indicate the holds that are included in the route. To support his sort of creativity the climbing sections need to be heavily populated with holds to give a wide assortment of options. The rope elements can be hacked by using various loose parts like planks or obstacles or even by taping.

There is nothing about this playground proposal that is outside the capability of designers to develop, fabricators to make, contactors to install, or park and recreation professionals to understand, support, and program.

Today one would have to combine a professional challenge course with a climbing gym to get this level of congruence with the child’s developmental needs. However, all of the benefits can still be delivered if the structural elements are eight feet or less high, which makes it possible for such a playspace to be in any public park.

We could go on to use the chart to examine how seating is provided in parks, or sand boxes, or even standard play apparatus, but I think you get the point. Designing from the children’s way of knowing and the modalities they employ in their inquiries results in far more appealing projects than our traditional approach of using the adult’s criteria.

Source

connecting

Are you the Joshua Archer at locarie Games?

Play and Learning - Role-playing Games

Another form of inquiry learning that I have been involved with for many years is the use of role-playing games in educational contexts. yes, when I say 'role-playing games' , I mean games such as the infamous "Dungeons and Dragons" from the 1970's and 1980's, but today, the field includes so much more breadth of expression in both creativity, context and goals, that we could truly consider ourselves in a renaissance of the RPG. In my after school enrichment programs and summertime day camps, I've been using RPGs to teach kids about the world through a model/simulation that incorporates tons of social skills learning, as well as the "4 C's" of the 21st Century Skills movement (p21.org). How this falls into inquiry learning, is that the game creates a world in which the kids inhabit a persona, and work from that persona's assumptions and world view (training empathy in the process), but those persona act within the world with nearly limitless ability to direct the narrative. Decisions are made, actions are performed, and consequences of those actions are followed through, all at the whim and decisioning power of the players. It is, at essence, a modeled discover/inquiry game that leads the players through a simulation that in itself can teach so much content and process, including, but not limited to: math, science, history, language arts, performing arts, collaboration, cooperation, communication, creativity, logical problem solving... the list goes on. I'd love a chance to talk to you about it for your program, if you are interested (and you can reach me through Michael, as we're in our Masters program together.)