Age Differences should be remembered when planning

Playground planners working within the United States have a variety of in-depth resources, suggested guidelines and safety performance specifications from which to use when designing or constructing playground equipment. The general aim of these resources are to assist the reader in creating safe and protected play experiences for a child or a group of children. This article identifies key characteristics of children at three different age levels to ensure that the playground is not only age appropriate according to the child's physical abilities, but also reflective of the child's social and cognitive abilities. All three domains should be considered when creating new playground designs, and especially when deciding who should play on an existing piece of equipment. The latter is a decision made daily, and sometimes arbitrarily, by playground teachers, supervisors, and parents across the country.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CHILD CHARACTERISTICS

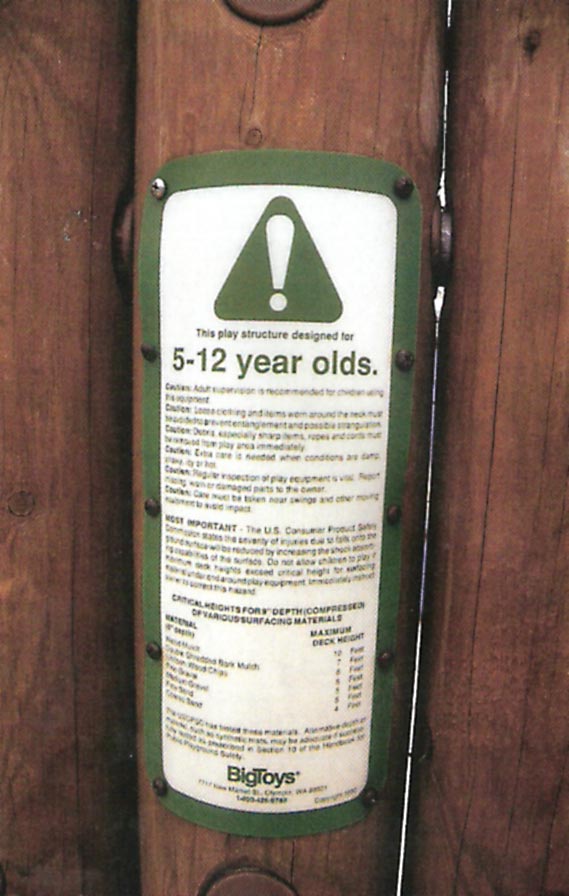

Since the early 1900s, playgrounds have been built to provide adequate space for children to release energy, socialize with friends, acquire understandings about the outdoors, and most of all to have fun. According to the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission's (CPSC) statistics, nearly 200, 000 playground-related injuries require emergency room visits every year. The majority of these injuries are related to age-inappropriate use of the play equipment. In other words, children ages two to four are playing on equipment designed for children five to 12 years old, and the latter group is using equipment designed for younger children in inappropriate ways.

Some items on the play structure facilitate cognitive play and aid in the development of the child.

There are two fundamental reasons for this situation to occur. First, it is critical to remember that children naturally seek challenges and learning experiences as they play, and after obtaining a level of success they instinctively seek the next level of difficulty for a new and greater challenge. Most motivation and early childhood theorists agree that children process a fundamental human urge to be competent and independent learners, to control their environment (Donaldson, 1979). This inherent urge to achieve greater levels of difficulty is the foundation from which we base our educational offerings in USA schools today.

Unfortunately, playground challenges offer physical risks and dangers unlike the interactions and cognitive tasks stemming from classroom books and materials. Therefore, supervisors and designers must place an even greater importance on common childhood characteristics to ensure that the equipment is designed with a particular age in mind and that the design offers a significant number of challenges for continual use. This awareness will help ensure that each piece of playground equipment is used according

to its intended purpose.

AGE-APPROPRIATE PLAY CONSIDERATIONS

To assist the designer or supervisor in recognizing several fundamental differences in childhood characteristics, the following examples discuss three imaginary children and their play patterns, as they relate to a playground setting. The first imaginary child is two-year-old "Jack." jack (See

Figure 1) manifests a desire for independence and mastery through periods of intense physical exploration. He is able to use words to represent people and objects and is most happy when a playground's equipment provides for perceptual motor activities such as feeling and grasping, crawling and exploring, and simple balance challenges (Frost and Klein, 1989). Gradual sloping ramps, platforms, and inclines that include a variety of ways by which Jack can ascend and descend, as well as rubber tires embedded vertically in the ground stimulate his desire to continually explore. He is happy to play alone or alongside one other playmate.

"Jill" (See Figure 2) is age four and attends a local preschool. Much of her play focuses on fantasy and imitation. Play to a four-year-old is a way to create a sense of mastery over both immediate and imaginary situations (Erikson, 1950; 1963). Jill has developed a sense of self and her personality has become increasingly autonomous. Problem-solving by trial and error at age four evolves into elaborate role-play scenarios on favorite concrete structures resembling animals, sea life or insects. Playhouse packages also provide a steady series of challenges for her small group interactions with playmates, and she has increasingly developed the ability to attend to more than one attribute of an object or a situation. Her increased language ability assists her in understanding playground rules, however, she finds it difficult to respond to "how" "why" and "when" questions. She has established a hand dominance, and she feels accomplishment when climbing to the top of a five-foot slide when using a tire swing that is supported from three points, or a spiral platform, wooden or rope ladders, and cargo nets. When given a choice, she is more likely to choose the same-sex playgroup as she establishes her gender identity.

"Jeff" (See Figure 3) is eight years old and in third grade. Unlike his two siblings, he shares an in-depth relationship with adults, peers and the physical environment. He has moved from the egocentrism common to Jill's behavior to an awareness of his strengths and weaknesses both as an individual, and as a member of the peer group. The desire to be a part of a peer group is likely to cause Jeff to display and test his physical abilities. Many of his physical feats will be aimed at his ability to manipulate different pieces of equipment. It is likely he will test his ability to hang from, climb up, crawl through, stretch beyond, and perform balance feats that coincide with, or extend beyond, his physical maturation since his movement skills still need to be refined. Daily physical activity is necessary for Jeff to increase his small and large muscle skills. Increased self-esteem is acquired through his newly developed physical strength, power, and agility. His physical prowess and eagerness to control his environment can no longer be satisfied in activities that do not peak his curiosity. Jeff's cognitive and social interests are best sustained through playground pieces that afford some physical and mental test. Examples include playground equipment that offers increasingly greater heights to conquer, greater tests of strength while swinging from pole to pole, or hanging from a track ride.

It is best when specific information is included on the structure that gives details about use.

SUMMARY

Incorporating the child's social and cognitive behaviors when selecting, designing, or supervising a playground is one element to consider when deciding the most age-appropriate playground equipment for a child or a group of children. It also assists playground supervisors in predicting the value of a particular piece of equipment. In all cases, the user's social and cognitive pursuits, as well as their physical abilities, influence the extent to which a child plays safely and finds enjoyment in a piece of playground equipment.

Margot Brous is an adjunct professor at Hofstra University in New York and is a playground safety consultant with Playground Safety Solutions. She is an NPSl-certified playground safety inspector and is a member of the American Association for the Child's Right to Play.

Rhonda Clements, Ed.D.1 is currently the president of the American Association for the Child's Right to Play. She is an associate professor and the coordinator of Graduate Physical Education at Hofstra University in New York. She has authored five books on the topic of movement, games and play activities for children.

REFERENCES:

- Bjorklund, D.F. (1989). Children thinking: Developmental function and individual differences. Pacific Grove, California: Brooks/Cole

- Christiansen, M. & Vogelsang. (1996). Play it safe: An anthology of playground safety. (Eds.) Arlington, Virginia: The National Recreation and Parks Association.

- Clements, R. & Schiemer, S. (1993). Let's move, let's play: developmentally appropriate movement and classroom activities for preschool children. Reston, Virginia: The American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance Publications.

- Curtis, S.R. (1982). The joy of movement in early childhood. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Donaldson, M. (1979). Children's minds. New York: Norton.

- Erikson, E.H. (1950/1963). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

- Frost, J.L. & Klein, B. (1989). Children's play and playgrounds. Austin, Texas: Playgrounds International.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (1981). A handbook for public playground safety'; Vol. 7: General guidelines for new existing playgrounds. Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

Add new comment