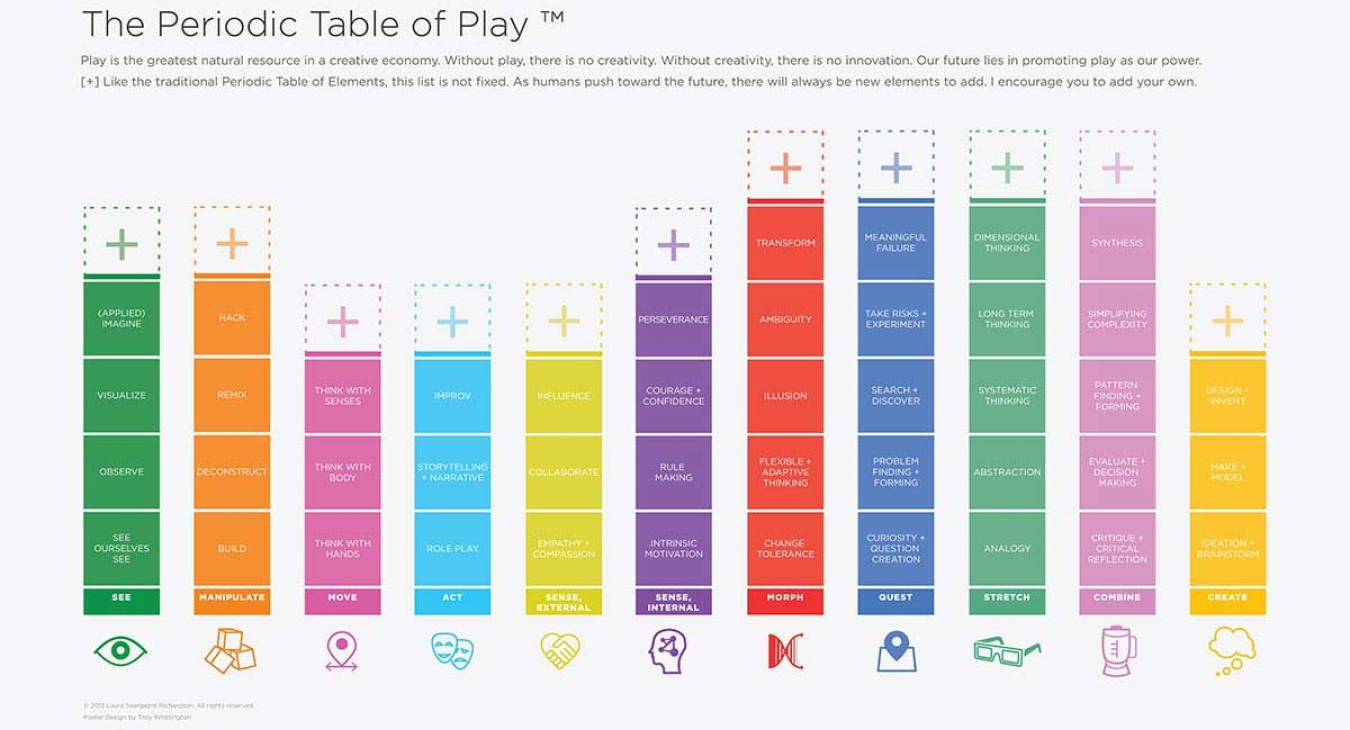

The Periodic Table of 21st Century Play - by Laura Richardson

There have been many philosophers and researchers who have made play a central subject of their work: Piaget, Huizinga, Rogers, Parten, Bruner, Dewey, Montessori, Vygotsky and many more. These thinkers have enlightened us and given us new insights to guide psychotherapy, education, and parenting. As important and useful as these contributions have been, they all share one quality that has limited their impact on society and culture, they are conceptual “silos.”

I’m going to guess that, for many readers, the term “silo” brings up images of grain storage facilities along railroad tracks out in the Great Plains. Over the past decade or so the term has become associated with a way of organizing information, in which it refers to data that is primarily not shared and is built up in a step-wise manner. With the advent of the Internet, more and more information is horizontal, in which data is stored and accessed in as a wide and diverse way as possible.

This idea of silos applies to previous work on play in that the theories remained for the most part limited to the disciplines from which they arose; i.e. early childhood educators know about Piaget, but his ideas have very little currency outside of that circle.

That situation is changing and changing rapidly. In today’s interconnected world a new type of thinking, horizontal, is gaining rapid acceptance. People talk about systems approaches, emerging knowledge, transformative and disruptive innovation.

Recently Laura Richardson published The Periodic Table of 21st Century Play. This is a perfect example of horizontal thinking in that it encapsulates the essential experiences of the whole child. Each category is shown in the full spectrum of its development from the core experience to its expression when fully matured. The Table is also a perfect expression of the current mode of thinking in that this is not a rigid chart with milestones, but an open “thought problem” which Laura encourages the reader to explore and elaborate.

Laura is not an educator or a developmental psychologist. She refers to her work as a “customer experience strategies and design.” To do her job she must think very deeply about what factors engage people. It is not surprising therefore that her work and her interest in play grow out of the same passion.

The significance of Laura’s work is that it is not part of a traditional channel of research, but is part of her practice that reaches across all sectors of society and business. Not only are her clients diverse, but also the questions they ask and the projects that are undertaken are equally diverse.

Laura’s contribution is that “Playful Thinking” has broken out of its silos and is loose and free. Her ideas allow for creativity to blossom into all sectors of society and for the power of play to find its day in the sun.

I’ve written previously about what I call the “Play Avoidance Syndrome,” where the talk about play heads off into concerns for safety on one hand and into intellectual discussions on the other. In keeping with this notion, I thought the best way to explore Laura’s ideas was to try them out with kids. The opportunity came up this week when I gave a talk to a local continuation high school class. These students tend to be challenged to find a way to get traction in life, and they are especially receptive to “out of the box” thinking.

In the presentation, I used Laura’s approach to the ideas that she demonstrated to me by substituting the term “superpowers” for “play.” This approach really grabbed their attention, and I asked all the students to pick one superpower that they would like to develop. One student chose “improv” as the superpower they wanted. We then talked about how that power would help them in their future career.

The discussion quickly turned to: “How do I get a superpower?” The way the table is set up helped us look at the basis of improvisation, starting with “act” and moving through “role play” and “storytelling.” In essence, the Table gave us, in just a few minutes, a prioritized action plan that made sense to the student. By breaking play (superpower) into tangible elements, the value becomes more apparent and we could focus and choose which element to amplify.

The table shows that superpowers are not just physical, but also mental and emotional. This allows the students, and the teacher especially, to see playful learning beyond textbooks, recess, and homework.

Unlike most other experiences at school, in the table, there are no milestones, no tests, or judgment. All the superpowers are equal. What was especially powerful about using the table was that it talked about important life skills that are rarely if ever, part of the students’ normal academic life. Since many of these students struggle with the typical “silos” of math, English, history, etc., these ideas offer an alternative way of looking at the future. As such, it provides a framework around which curriculum can be developed.

While this week’s experience was all about education, I also think that Laura’s ideas can open up new ways to improve playgrounds, and I will discuss this idea in my next column.