Climbing a slide - unintended use - Shutterstock 102166951

Background Information on Developments within the ASTM F1487 Standard

On May 20, 2013 the ASTM F15.29 Subcommittee responsible for the content of the ASTM F1487 standard received a letter from the staff of the U. S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). CPSC staff noted that the specific types of playground equipment in Section 8 of the Standard (balance beams, climbers, upper body equipment, sliding poles, slides, swings, swinging gates, merry-go-rounds/whirls, roller slides, seesaws, spring rockers, log rolls, track rides, roofs, and stepping forms) were not defined in the terminology section of the standard. CPSC acknowledged the difficulty in defining these items but felt the lack of definitions may lead to differences in interpretations and application of the standard, resulting in some products not meeting the appropriate specific equipment performance requirements.

Prior to this 2013 letter, the CPSC staff submitted a written comment on a May 2012 ballot item that proposed to add a new Section 8.0 to ASTM F1487 to address new equipment designs not currently being addressed in specific performance requirements in the current Standard Section 8-Equipment and Section 9-Layout.

The proposed ballot item was to address all the new innovative equipment that does not fit neatly into the existing equipment categories or types. CPSC and ASTM agree, all non-traditional equipment not specifically identified in Section 8 still need to be evaluated using this standard. Everyone currently involved in writing playground performance standards understands industry innovation is moving at break neck speed. This is a good thing for children. The ASTM F15.29 Subcommittee wanted to minimize the likelihood of life-threatening or debilitating injuries from innovative non-traditional equipment by directing designers and manufacturers to apply all general performance requirements in all the Sections leading up to Section 8 of the standard and evaluate the equipment for any potential hazards.

CPSC staff has serious concerns about the implication of exempting all equipment, not of a specific type, from all of the equipment performance requirements currently contained in Section 8 and 9. CPSC staff believed this ballot item did not provide the guidance required to adequately eliminate or reduce the potential risk of injury from “non-traditional” equipment. CPSC staff believed this proposal provides a loophole that may allow potentially hazardous products to enter the marketplace. The basis for their concerns were spelled out in 3 points within the CPSC staff’s written comment to ASTM F15.29 Ballot F15 (12-03), Item 6, dated May 10, 2012:

“1. Section 8, Equipment, contains performance requirements for the following specific types of playground equipment: balance beams, climbers, upper body equipment, sliding poles, slides, swings, swinging gates, merry-go-rounds/whirls, roller slides, seesaws, spring rockers, log rolls, track rides, roofs, and stepping forms. The equipment types, however, are not defined in Section 3, Definitions. This leaves their definition open to interpretation and could allow equipment to be considered to pass the standard by a manufacturer, test lab, or consumer who asserts that the equipment was not mentioned specifically. For example, there is no definition for “balance beam.” If someone were to place a long, flat beam between two posts, 20 inches from the ground, could that person then claim it was not a balance beam because it is more than 16 inches from the ground, and therefore, covered by the proposed exemption? If the answer is “yes,” then CPSC staff strongly disagrees and feels this exemption would seriously undermine the spirit of the voluntary standard.

2. The “Climber” and “Upper Body Equipment” sections have generally served as the “catch-all” categories for equipment that does not fit elsewhere. This exemption will allow equipment to avoid even those requirements.

3. This ballot item states that nontraditional equipment need only meet the “general performance requirements.” There is no section for “general performance requirements,” however, Section 5, “General Requirements,” contains only three specific requirements limited to age grouping, anchoring, and small parts (15 CFR 1501); and Section 6 “Performance Requirements,” contains a limited number of performance requirements. As written, it is unclear how Sections 5 and 6 apply and whether Sections 9–15 apply at all.

CPSC staff believes that rather than exempting nontraditional equipment from most aspects of the standard, a more appropriate method of dealing with any issues of nontraditional equipment would be to focus on the hazards posed by the equipment. For example, one of the newer types of playground equipment, perhaps one considered by the subcommittee while discussing this ballot item, is an overhead spinner that children hold while spinning. The 1990 COMSIS

The CPSC staff acknowledged over the past few years the design of playground equipment has undergone some radical innovations. They are in favor of innovations in playgrounds and believe playgrounds serve an important function in childhood development. They state in the letter,

“Playgrounds should allow children to develop physical and social skills, and part of that development includes testing the limits of their skills. Innovation is important for this, as children need new challenges. Staff believes it is important that new, innovative playground components should still follow the safety recommendations and standards that both CPSC staff and ASTM have worked to refine over the past several decades.”

The CPSC staff stated their concern with new innovations that are labeled as “climbers” and yet these climbers appear to be used by children as a sliding surface. Their initial concern with this type of equipment was the lack of time between when the product is released in the marketplace and the time required to create any kind of reliable injury statistics specifically pertaining to what may be considered by some as slides and labeled as climbers by a designer/manufacturer. Another issue they raised was how these new designs are identified, categorized, and finally entered into the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) database by someone with little or no experience in all the current types and variation of public play components. The NEISS system has been around a long time and this coding system may need to be looked at again for its relevance to today’s circumstances. The current coding system makes it difficult for the CPSC to differentiate data for these products from that of traditional slides. CPSC staff was made aware of incidents described as involving slides (such as “slid off side of slide,” “fell off slide while sliding down”), yet further investigation revealed the product involved was called or labeled as a “climber.” Our major concern with trying to define these new types of play equipment is the definition needs to be very vague to not become design restrictive beyond the intended design use. The problems arise when the standards writing organizations begin to try to create performance specifications that are not design restrictive yet still address the injury patterns on a particular type of play event. It seems to me that what we call something is not the answer. The bigger issue seems to me to be how the users play and interact with it that is most important when it comes to the assessment of safety issues versus the need for challenge and risk in the play environment.

Many of us may remember a product labeled by almost everyone in the industry as a “banister slide.” They are still being sold today. Jay Beckwith recently pointed out in his Playground Professionals column that during the R and D on this component the designers/manufacturers asked, “How are the kids supposed to use this?” His response was something like don’t worry, they will figure it out. The point is, we cannot will a child to do anything the same way each and every time in an open free play environment. Once they figure out how they can use it, which may be the designer’s intended design use, they will master it. Then when boredom sets in, they will begin to look for other ways to interact and use it the next time, and the next time after that, and so on. Usually this kind of process and experimentation evolves into more risky play behavior as the user’s desire to experience the thrill of the challenge. I challenge you to go out and play and try this little experiment. Go to a local playground that has a balance beam. Walk across a balance beam once or twice. Then try it again with your eyes closed. Which was easier? What were you thinking when you had your eyes closed? Could you do it? Did you peek? Were you scared? Did you feel your pulse rate increase? As we get older our desire for this kind of excitement unfortunately begins to dwindle but not in children. Most thrive on this kind of excitement and challenge. Imagine this same “balance beam” experience if the designer places a properly designed handrail on each side of the beam. It would be much safer and almost guarantee a successful outcome regardless of your balance skills or whether or not you had your eyes closed. Building codes and ordinances take this approach for the health and safety of the general public in residential, public institutions, and commercial buildings. This is not the approach to be taken in the design of a public playground or the development of playground safety performance standards. We want as much safety factored into the design as necessary but as little as possible to address debilitating and life-threatening injuries. The concept for “not too much and not too little” causes the angst being felt by playground owners, designers, manufacturers and all who inspect, maintain, and repair these facilities. Injury data has led to some play components requiring handrails and handgrips on access components and guardrails and barriers on platforms above a certain height. Have we gone too far? Does anyone think a child would find a balance beam with handrails challenging or fun? I think the child is more likely to climb up on the handrails and attempt to walk across them. I would call this “unintended design use” or “reasonable foreseeable misuse” with “unintended consequences.” Ultimately we come back to the point of determining how much safety or risk is enough and how much of either is too much.

Play equipment definitions versus its intended use and reasonable foreseeable misuse

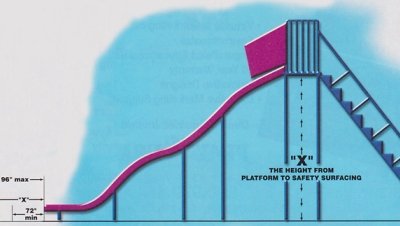

Is a banister slide really a slide? Does an inclined board of say 20 degree slope constitute a slide in the traditional form? What slope is necessary before you truly can have any kind of meaningful sliding experience? If this board doesn’t have a point of reduced gradient or 4 inch side rails with proper slide exit heights and transition platform of at least 14 inches deep, does it mean it is not a slide? This gets to the CPSC staff’s concern. How does an inspector evaluate a piece of equipment when it does not meet all the requirements for a specific piece of equipment based on what the designer calls it or what an inspector labels it? I would agree that a slide with only 20 degree slope would not be used for sliding as much as it might be used for climbing. What slope is required before a child will involuntary begin to slide down the surface because of gravity?

In Part 2 I we will look at the CPSC’s traditional definition of a slide and the reasonable foreseeable misuse of the slide from a child’s perspective. I will present some options to consider on how to evaluate a piece of equipment regardless of labels.

Source

Challenge

This is an important discussion that will require some very creative thinking. Reading this I though of the many times I've seen kids go up a slide, or jump out of a swing, or perch on the top of monkey bars. To design apparatus based on name is ridiculous yet the issue of being able to track injuries is also very real.